Rawabi, Palestine’s first planned city, enters new phase

Palestine Monitor - Lili Martinez - Sitting on the purple couch in her brand-new, three-bedroom apartment, Hanaa Kamal gestures enthusiastically as she describes her family’s experience as one of the first to move into Palestine’s first planned city, Rawabi.

“My initial expectations came true and more … it’s more beautiful than in pictures and movies,” she told Palestine Monitor. “All the things they promised us, they have delivered even more.”

Hanaa and her family moved into their apartment in Rawabi a year ago, when the city was still a ghost town. Now, though, Hanaa says she has plenty of neighbors, and more are on the way.

“The more people we live with, the more I feel that the idea is really good,” she explained. “When we were alone, we felt it was an empty place. But with more people coming, we started to feel like there are really distinguished people to choose this place.”

Hanaa Kamal waters plants on her balcony in her new apartment in Rawabi, which her family moved into last August

The family used to live in El-Masyoun, in Ramallah. They chose Rawabi partly because Hanaa’s husband works at Massar, the company that is of two main investors in Rawabi. But Hanaa says there were other reasons, too. “You can feel safe when you leave your kids here,” she explained. “In El-Masyoun, my kids refused to go down to play, but here, they refuse to come up.”

And although Rawabi still doesn’t have a single coffee shop or retail store, Hanaa isn’t worried. “Everybody loves Rawabi and everybody comes to visit. They wonder why they didn’t go with this idea from the beginning. When we moved, my friends told me they wouldn’t come visit because Rawabi is too far away. Now, they come here to spend the night and play with the kids.” Step by step, Hanaa reasoned, the city will add facilities. “Now we have the pharmacy, the laundry, the

supermarket. Soon, other things will come, all in time.”

The city is not finished, but it’s well on its way. With 250 apartments sold and almost 1,000 more in construction, Rawabi’s developers are selling it as an oasis of calm and organized living. But the story of Rawabi has not been without setbacks.

Conceived in 2007 by Palestinian billionaire Bashar al-Masri, Rawabi, which will have 25,000 residents when the first stage of building is complete, is “the biggest investment in real estate in Palestine now,” according to one of its architects, Ibrahim Natour. So far, he told Palestine Monitor, Masri’s company Massar and its main partner, Qatari Diar, have sunk $1.2 billion into the city.

Construction cranes still loom over Rawabi, and the downtown area is not yet operational. When complete, it will boast a convention center and large hotel.

Nine years later, the city’s development is not exactly on schedule. Most of the major delays have stemmed from the challenges of building a city under occupation. The two main problems: installing a working water line and building a road to connect the city to the rest of the West Bank.

Although most of Rawabi is located in Area A, where the Palestinian Authority has full civil and military control, several areas of Rawabi, by necessity, are located in Area C, where the Israeli military holds control. To bring a water line into Rawabi, planners had to connect their line to Area C. Getting the necessary permits took years.

“When excavation started in 2009, we applied for a water supply road,” Natour explained to Palestine Monitor. “Since then and until May 2015, we had no water in Rawabi. We faced big problems because it was a big gamble.” Masri had already invested $1 million in the city, but even after selling out the first two neighborhoods, families were unable to move in because of the lack of water.

A BBC Worldwide documentary released in March 2015 chronicled the frustration and anxiety felt by Rawabi’s developers and the families slated to move in. Just two months after it was released, Rawabi’s water line was approved — for 300 cubic meters the day, about enough water to fill a swimming pool. “We solved the problem of laying down the line but we still have the problem of the quantity,” Natour sighed.

Rawabi’s second problem stretches from its entrance to the main highway: the access road. A narrow, two-lane road, Natour describes it as “not decent for a city.” They hoped to build a wide, four-lane road, but permits from the Israeli civil administration have not been forthcoming. Most of the road, too, lies in Area C.

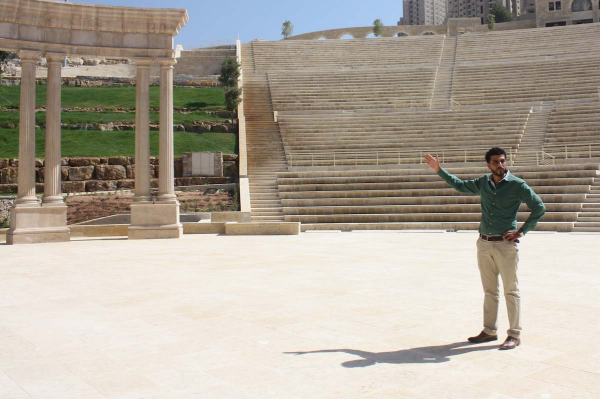

Despite these two setbacks, construction is now moving ahead. Two neighborhoods have been completed and one is finally full of residents, with two more on the way. A school, a mosque, the municipality building and the hospital are all in various stages of completion. Rawabi Park, which Natour describes as “the largest entertainment area in the West Bank” will, when complete, boast an amphitheater that can seat 15,000, a plug-and-play stage, restaurants, bungee jumping, 4x4 trails, a Bedouin tent and perhaps even a water park.

Ibrahim Natour, a chief architect of Rawabi's Roman amphitheater, which seats 15,000, explains its design

The center of the city will boast shops, restaurants, and a business area. Easy staircase access from each neighborhood will connect residents to the heart of the city. Rawabi’s developers hope to bring international brands to Rawabi, and have recently signed deals with as-yet unnamed companies.

In one of the completed neighborhoods, children play on a brand-new playground between two apartment buildings. The neighborhoods are modeled after traditional Palestinian “hays” which are semi-private, with public gathering spaces for residents. There are nooks for sitting, exercise machines, and basketball courts open to all. No wires stretch between the houses — Rawabi’s infrastructure is entirely underground, with networks for water, sewage, electricity and telecommunications, among others. According to Natour, apartments sell for up to 30% less than their equivalents in Ramallah.

Children play on one of Rawabi's many playgrounds, which are located in small areas between apartment buildings

Rawabi might seem like a utopia at first glance. But its critics call it a “Palestinian settlement” and say building such a city in an occupied land undercuts advocates of the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions) movement and glosses over the suffering Palestinians experience under occupation.

Natour dismisses these claims. “We have a problem with the occupation,” he told Palestine Monitor. “We are not sugarcoating it. Regarding the BDS issue, yes, we use Israeli materials, but they are the same materials that Ramallah and all the West Bank take from Israel.”

As to whether Rawabi is a settlement, Natour retorted: “We feel proud about this. The Palestinian community has always been in the valleys and the Israelis took all the hilltops. Should we keep ourselves on the valleys and leave the hilltops for them?”

Despite its critics, however, Rawabi is moving forward. As the summer draws to a close, the city seems to be entering a new stage in its development. The first school is set to open in September, and hundreds of new residents will move in by November. And last month, Palestinian Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah visited the site for the first time since construction began.

“The government has always been supportive of Rawabi, but its resources are limited,” Natour explained. “Mr. Hamdallah promised to start implementing the project here and to consider Rawabi a full-scale municipality, to start the government’s role in this city.”

Natour told Palestine Monitor the team hopes to focus on the future of Rawabi, and to emphasize the accomplishment they have achieved in building it. “We want everyone to come and see that we are part of state-building. We can run a city. We are not what your TV is saying about us, or what your politicians are saying about us. We are good, developed, civilized people who are living, building, like you.”

Hanaa feels the same. “Some people told me no, in our country because of the occupation you can’t have this. But over time Rawabi has proven to be our dream. To live in a calm, quiet, new place with all the modern facilities, is our dream. Rawabi, it’s not a luxury anymore. It’s a must. We have to have a good place to live.”

Bashar al-Masri did not respond to requests for comment.

To view original article, Click Here.